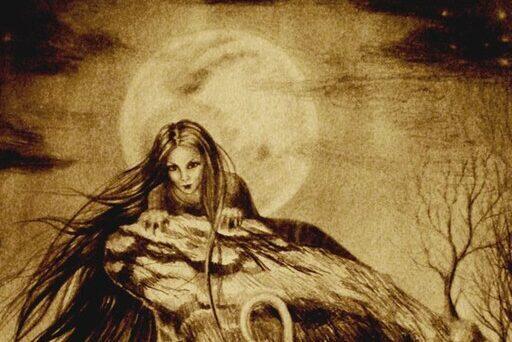

In that dead hour of the morning, the last before the horizon begins to blush with the dawning sun, when the cold and the shadows are deepest, a spindly figure crawls over the crest of a northern hill to gaze upon the villages below. Her hair is darker than the surrounding moonless night and gnarled in unworkable, wiry mats. It tumbles around a malnourished figure, seemingly forced onto her hands beneath her own meager weight. She is unshapely and clothed in black rags. The maiden’s arms, though bony and feeble, end not in dainty hands but with the large paw of a wolf. Her face is pale and sallow, the skin gauntly stretching over what would be elegant bones. She seems at once both an ill youth and a haggard crone.

The monster’s canine claws dig hungrily into the earth, as she surveys each farmer’s domain, conspiring how to worm into the homes of hapless peasants and sew exquisite destruction. But it is not yet time.

She flicks a tongue over her fangs and waits, her power growing with every moment. Inhuman eyes—cat-like pupils amid a pool of glowing yellow—flick to a bed of plants below. There, stands a sole bloom; one single, persistent flower. The creature watches patiently, ravenously as frost begins to crystallize on its innocent, violet petals. The bloom bends and then crinkles. Its color fades and it sinks to the ground.

Morena, goddess of death, night and winter, then beams with a wicked smile. She rises and with force unimaginable from such a pathetic body springs forward, bounding into the valley. For now, it is her domain.

A while ago, I had the opportunity to learn about the ancient rituals surrounding the Slavic goddess Morena. With song and skit, performing students depicted the pagan traditions that their ancestors had practiced. These peoples’ hatred for the witch of winter ran so deep that every spring they would hold a festival to purge the land of her evil.

During these celebrations, Slavic villagers would leap over large fires, allowing the licking flames to cleanse their souls. A cloth and straw doll, often put together by the village children, would be dressed to look like a young girl. This was meant to represent Morena. The Slavs would then parade the effigy to the nearest lake or river, set her ablaze and/or tear her clothing, then symbolically drown her in the water. This released them from the grasp of winter and allowed spring to return. (A responsibility we Americans have since delegated to a groundhog.)

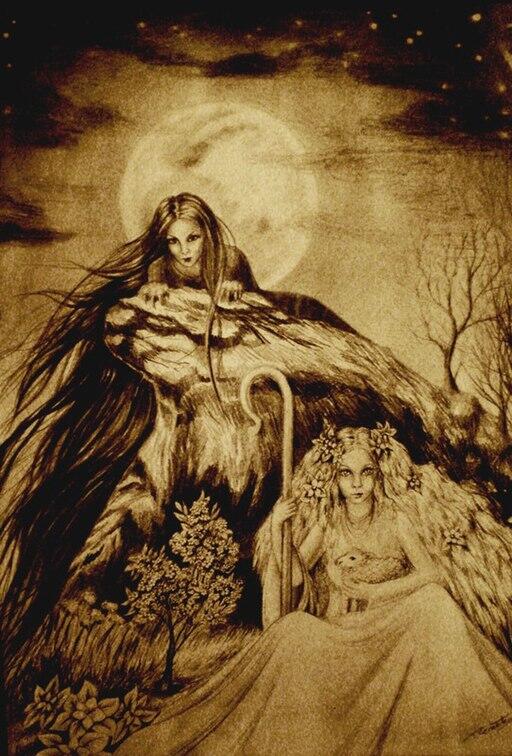

To them, the exile of Morena was also an invitation to Vesna, the goddess of spring and fertility. The two powers—life and death, winter and spring—could exist in the same place at the same time. Therefore, as Morena fled the villagers’ march, Vesna would waltz back into the land, bringing prosperity in her wake.

Flames climb the straw and cloth body of the doll, crackling and sputtering behind as it moves through the forest. Adorned in the garb of a young girl and held aloft by a man with a tree branch, the effigy leads a singing and dancing, jovial parade of people. It has been a hard winter, but their village escaped without many losses. They had won against nature and celebrate the coming abundance. For spring is nearing.

Up the path, on all fours, Morena flees from the villagers, stumbling over paws which have suddenly become useless and heavy. She struggles to carry herself forward, but fear of the pain pursuing her pushes the witch on. Even so, she cannot escape the passion in the songs resounding behind her. She each word as a spear through her heart.

Morena skids across the sandy-soil of the river bank, halting just short of the swift water. She climbs a boulder, gasping for air, but, out of desperation, coils up and tries to jump the water anyway. The villagers, now in sight of the river as well, give a cheer! Their cry sends the goddess tumbling into the rapids, where she fails helplessly against the current. As the villagers reach the bank, they grow louder and happier, then dunk the flaming doll into the water, banishing winter in that moment. Down the violent flow, Morena’s head bobs out one last time, with a wretched gasp, then does not again break the surface.

Away from the celebrations, a blushing face looks onward. She hides behind a tree whose bark seems to mold with the lush hazel hair that cascades over her shoulders to her waist below. She giggles, bringing a soft hand to her lips. The laugh reaches expressive eyes the color of sunlight through the leaves. Her full figure stands nude below—as if born from—the spring’s first budding tree.